Solo Exhibition at Floating Goose Studios

Fragile Bodies

Catalogue essay by Jess Taylor

It is no random thing that our enduring tales are cautionary ones; for all our progress and reason, we remain creatures driven by instincts and anxieties. In some ways, to fear is to be human. And as much as it is in our nature to fear, it’s in our nature to seek to conquer fear, to embrace it, to look the fearful in the eye and dip our toes into it.

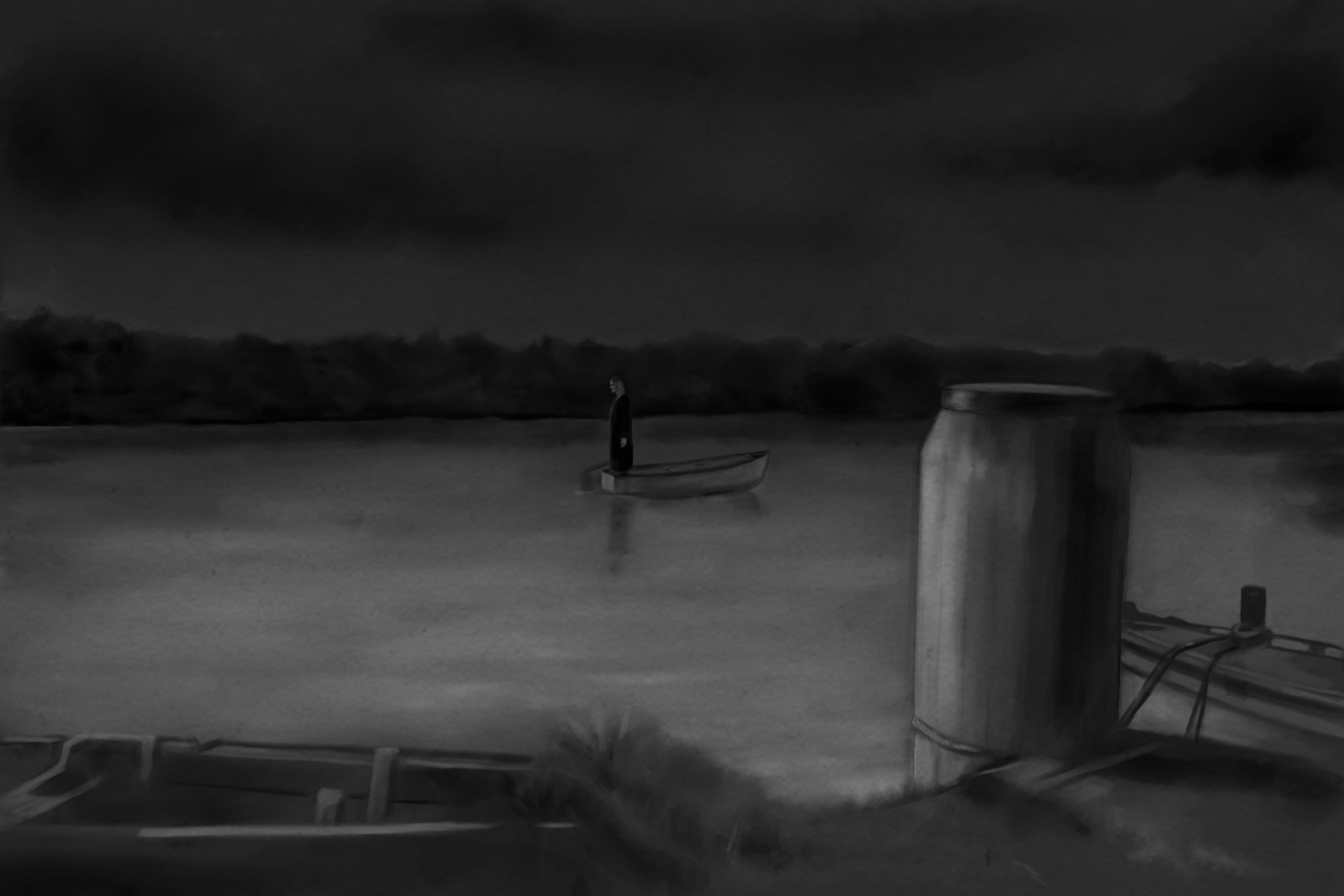

Looking at Beckinsale’s works, I’m reminded of one of our most prolific fears; the fear that our bodies are not as impervious as we would like, that we are vulnerable creatures, and that there exist beings and forces more than capable of exerting their will upon us. It is the realisation that the control, the reason we so steadfastly believed in might have been a trick of the light, that the lives we build will only ever be delicate things, one happenstance away from collapse. This fear is the experience of looking down at our bodies and thinking, “fuck, this is going to be the thing that kills me,” of standing on a beach or a jetty or a boat where the sea and the sky occupy your entire periphery and realising the sea could devour you whole, secreting you away forever in an act of human profundity and oceanic ambivalence.

This kind of fear is one of my favourites because it is an isolating fear. When you face nature at her most sublime, our biggest strength – strength in numbers – washes away; we face the extraordinary alone, our core singular humanity singled out to be measured against the inconceivable.

There is certainly an element of the overwhelming in the space of this exhibition, in Beckinsale’s almost life-size figures and the vast vistas they occupy. Inky black, particularly within the architectural space, operates two ways; it becomes the void, and emptiness that expands walls ever out, or it becomes limiting, oppressive, absorbing light and space until the walls close in around us. In this space we feel the sea on our skin, simultaneously an infinite emptiness that hides a multitude of horrors and a terrible expanse that presses in around us, her fingers digging into our flesh and worming into our throats.

These works remind me that as well as being a fearful species, we are a lonely one. Indeed, loneliness looms large in the current time and in these works, in the singular figures dwarfed by the natural world, in the gaze of the artist surveying a space devoid of human life. It’s there in the delicacy of hands and the multitude of emotions conveyed through gesture, through the contraction and expansion of ligaments, in the way we read

intent before thought and identity without an anchor, in our desire to touch, to reach, to hold. Loneliness is in the distance between us and these figures, in our singular humanity being subsumed by forces outside of our control, more heart wrenching in this, the age of isolation.

At its most abstract, our loneliness and our desire to sate it through companionship is what drives humans all over the world to personify the sea. I look at these works, and I see myself – who I am, who I’m afraid to be, and who I wish I was. I’m in the body strewn on the beach, I am the viewer looking at the woman, too at one with the sea to be natural, I am the rocks the sea breaks upon, the great survivor, I am the man on the boat for whom the water is a balm to ravages wrought upon me, I am gesture, I am intent. And for as many times as I see myself, I see who I’m not, the things whose edges let me know where mine are, the horizons that separate me from things bigger, vaster, more ferocious than me, a dynamic other that brings my being into focus.

We personify the sea in order to contain her, to reduce the magnitude of her meanings into something our human minds can comprehend; we want to see and understand, just as we want to be seen and understood. That is not to say that we succeed where the sea is concerned; there is no small reason that we can look at these works and feel a palpable isolation, that we can look at the sea and long, that she calls to us in moments of darkness and that all through the millions of poems and paintings and stories she still slips from our grasp, formidable in her power.

Perhaps I can amend my previous statement that it is human to want to know fear, rather than to conquer it. The wise among us know that fear is not a beast to be slain but rather an exotic pet to be lived with, something that weaves itself into the fabric of our lives, making a home there. Witnessing these works, I know Beckinsale loves the sea, evidenced in the reverence she renders it in, the grandeur she ascribes it. More than that, she knows that the things we love are never static throughout our lives, that clear skies can darken, and that sometimes growing up means seeing dreadful dimensions in the places that once brought only comfort. These works are odes to dread and to change, to turbulence and loneliness, to the fact that nothing worth loving is one dimensional. They are artefacts of the hard work, the only work, the most pertinent work in these times; that of learning to live with fear, with ourselves, with the breadth of our lonely,

vulnerable humanity.